Advent of Code 2025 - Day 10: Factory

Day 10 was a mathematical disguise wrapped in a factory automation problem. What looked like pathfinding turned out to be linear algebra - specifically, systems of equations that need Gaussian elimination to solve efficiently. At least, that’s what I thought until Part 2 humbled me.

The Problem

Factory machines have indicator lights and buttons. Each button toggles specific lights. Find the minimum button presses to configure all machines.

Example input: [.##.] (3) (1,3) (2) (2,3) (0,2) (0,1) {3,5,4,7}

[.##.]- Target light pattern (.= off,#= on)(3)- Button toggles light 3(1,3)- Button toggles lights 1 and 3{3,5,4,7}- Joltage requirements (ignore for Part 1)

Part 1: Binary Light Toggles

My first instinct: this feels like pathfinding. Use BFS to explore different button combinations, find the shortest path to the target state.

But wait: pressing a button twice returns you to the original state. This means we only care about pressing each button 0 times or 1 time. No need to consider “press button A three times” - that’s the same as pressing it once.

This transforms the problem from exponential state-space search into something much more elegant: a system of linear equations over GF(2) (binary field).

Parsing the input

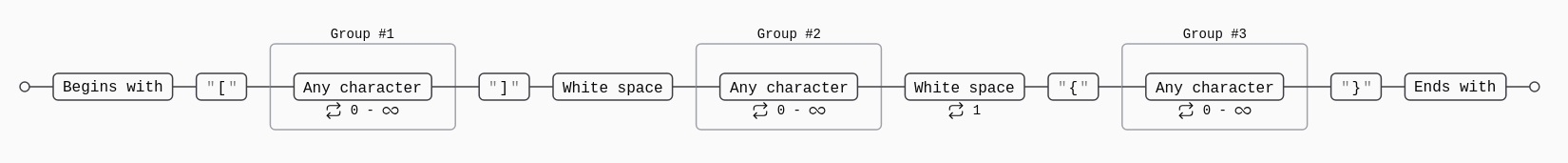

First, parsing with regex (because I’m not falling for “ignore joltage requirements”):

|

|

Why Linear Equations?

Let’s say we have 4 lights and 3 buttons:

|

|

For each light, we can write an equation:

- Light 0: Only Button A affects it. Equation:

A = 0(don’t toggle it) - Light 1: Only Button B affects it. Equation:

B = 1(toggle it once) - Light 2: Buttons A and C affect it. Equation:

A + C = 1(total toggles should be odd) - Light 3: Buttons B and C affect it. Equation:

B + C = 0(total toggles should be even)

These are interconnected! We can’t solve them one at a time. This is where Gaussian elimination shines.

What is Gaussian Elimination?

It’s the algorithm you learned in algebra class for solving systems of equations. For our problem, we’re working in “mod 2” arithmetic (binary), where:

1 + 1 = 0(two toggles cancel out)- There’s no difference between addition and subtraction

- We use XOR instead of regular arithmetic

The Matrix Approach

Build an augmented matrix where each row is a light and each column is a button:

|

|

|

|

Gaussian Elimination with XOR

The key insight: in mod 2 arithmetic, (A+B=1) XOR (A+C=1) = (B+C=0) because the A’s cancel out.

|

|

The Free Variable Problem

Sometimes the system has multiple solutions:

|

|

Button 2 is a “free variable” - we can press it or not. We try all 2^k combinations (where k = number of free variables) and pick the one with minimum total presses:

|

|

First try! (After understanding the math)

Part 2: Integer Counters

Part 2 reveals the joltage requirements matter. Now buttons increment counters instead of toggling binary lights:

|

|

Find minimum presses to reach target values.

First Attempt: Gaussian Elimination Over Integers

“Easy,” I thought. “Same approach, just use regular arithmetic instead of XOR.”

I implemented integer Gaussian elimination. Then I tried to handle free variables the same way as Part 1 - iterate through all possible values:

|

|

Why This Failed

Problem 1: Exponential search space

Some inputs had 3 free variables. With max_free_val = 200, that’s 200³ = 8,000,000 combinations to try. My solution took 105 seconds for Part 2.

Problem 2: Wrong answer

I got 19457 but the correct answer was 18960. My arbitrary bound of 200 was causing issues.

Problem 3: The math is harder than it looks

After Gaussian elimination, you get equations with fractional coefficients:

|

|

For a valid solution, ALL of these must be:

- Non-negative (can’t press a button negative times)

- Integers (can’t press a button 2.5 times)

Look at x₄ = -2.5 + 0.5·x₇:

- For x₄ ≥ 0: need x₇ ≥ 5

- For x₄ to be integer: x₇ must be odd

Combined constraints across ALL equations create a complex feasible region. And we need to minimize the sum within that region.

This isn’t just “solve the equations” - it’s Integer Linear Programming (ILP), which is NP-hard in general.

Why Part 1 Worked But Part 2 Didn’t

| Aspect | Part 1 (Binary) | Part 2 (Integer) |

|---|---|---|

| Variable domain | {0, 1} | {0, 1, 2, 3, …} |

| Free variable search | 2^k combinations (small!) | Infinite possibilities |

| Finding minimum | Try all, pick best | Optimization problem |

| Complexity class | Polynomial | NP-hard |

In Part 1, even with 5 free variables, that’s only 32 combinations. In Part 2, free variables can be any non-negative integer - you can’t enumerate them all.

The Solution: Z3

Everyone on Reddit said “use Z3.” I didn’t know what that was.

Z3 is an SMT (Satisfiability Modulo Theories) solver. SMT extends the classic SAT (boolean satisfiability) problem to formulas involving integers, real numbers, arrays, bit vectors, and more.

From the official Z3 tutorial:

“Z3 is an efficient SMT solver with specialized algorithms for solving background theories. SMT solving enjoys a synergetic relationship with software analysis, verification and symbolic execution tools.”

Instead of writing algorithms to search through possibilities, you just:

- Declare variables

- Add constraints

- Ask it to find a solution (or minimize an objective)

Z3 in Action

The core of the Z3 solution is beautifully simple:

|

|

That’s it. No Gaussian elimination, no searching through combinations, no edge cases about integer divisibility or fractional coefficients.

Why Z3 Works

Z3 is a SAT/SMT solver. To understand what that means:

SAT (Boolean Satisfiability): Given a boolean formula like (a OR NOT b) AND (NOT a OR c), find values of a, b, c that make it true. This is NP-complete - computationally hard - but modern SAT solvers can handle millions of variables using clever techniques like CDCL (Conflict-Driven Clause Learning).

SMT (Satisfiability Modulo Theories): Extends SAT to richer domains - integers, real numbers, arrays, bit vectors. Instead of just booleans, you can have constraints like x + y == 10 and x >= 0.

From the University of Maryland’s course notes on SMT:

“SMT solvers are useful for more than finding solutions to a random set of equations – you just have to know how to encode your problem in a form that the SMT solver understands.”

Z3 combines SAT solving with specialized “theory solvers” for integers. When we call Optimize() with linear integer constraints, it’s essentially solving an Integer Linear Programming problem - but we don’t have to implement branch-and-bound or cutting planes ourselves.

Performance Comparison

|

|

Z3 is slightly slower on Part 1 (where Gaussian elimination is perfect), but 200x faster on Part 2 and actually gets the right answer.

The Math Behind It

Part 1: GF(2) (Galois Field of order 2)

Binary arithmetic where 1+1=0:

- Addition = XOR

- Subtraction = XOR (no difference!)

- Multiplication = AND

This is why XOR is perfect for “combining equations”:

|

|

Part 2: Integer Linear Programming

- Variables: non-negative integers

- Constraints: linear equations

- Objective: minimize sum

This is a well-studied optimization problem. Solvers like Z3 use techniques from decades of operations research: simplex method, branch-and-bound, cutting planes, etc.

The Lesson

Know when to reach for power tools. Gaussian elimination is elegant and efficient for Part 1. But Part 2 requires optimization over integers with non-negativity constraints - a fundamentally harder problem.

Z3 is amazing for constraint problems. I’d heard of SAT solvers but never used one. Now I understand why people reach for them - they turn “write a complex algorithm” into “describe what you want.”

Wrong answers teach you something. My 19457 (instead of 18960) came from buggy bounds in my brute-force search. Z3 doesn’t need bounds - it reasons about the constraints directly.

Reddit is helpful. When everyone says “use Z3,” there’s usually a good reason. Sometimes the best solution isn’t the clever algorithm you write yourself, but the library that someone smarter already wrote. I wasted a lot of time trying to make Gaussian elimination work, instead of taking the easy way of using Z3.

Twenty stars total. Sometimes the hardest part isn’t the algorithm - it’s recognizing when to let a solver do the hard thinking for you.